Papilio – Your partner for socially and emotionally strong children

Our vision

All children experience equality of opportunities. They unfold their potential and evolve to become socially and emotionally strong personalities. As a result, an empathetic community becomes a natural consequence.

Every child is the future!

Our mission

No child is responsible for the environment it is born into. Some children are neglected, deprived or excluded. Others experience strong encouragement of their personality.

We do not want this injustice in opportunities to continue.

Using our programs and in cooperation with our partners, we give all children in nurseries and primary schools, irrespective of origin and social background, the same development opportunities. We support them in dealing with their emotions, strengthening their social competencies and encouraging them to release their potential.

With this stable basis, children are better protected from negative developments such as behavioral disorders, mental health issues and even addiction and violence.

Moreover, the children’s health and educational prospects improve.

As socially and emotionally strong personalities, they can live a self-determined life. They enrich our society with empathy, stand up for justice and take on responsibility.

Together we will achieve social added value, for a fairer society with a bright future!

Prevention programmes for nurseries, day-care centres and primary schools

Papilio is a social corporation committed to encouraging children early on (= timely) in their development. Developmental support is the most effective contribution to preventing addiction and violence. We particularly care about children who are not born into ideal conditions. For these children, day-care is a second chance in life. To this end, Papilio creates and promotes prevention programmes and modules. In more detail, these are:

- Papilio-U3: Prevention programme for nurseries with under 3 year olds (créches); development 2017 - 2019.

- Papilio-3to6*: Prevention programme for day-care centres with 3 to 6 years olds; developed 2003.

- Papilio-ParentsClub: Module for pre-school teachers in day-care centres, for the involvement of parents.

- Papilio-Integration: Practical seminar for pre-school teachers in day-care centres and their interaction with children who have experienced flight and/or migration.

- Papilio-6to9: Prevention project, "Paula starts school" for primary schools and after-school care; development 2016 - spring 2019.

Papilio is a social company and recognised as non-profit.

The Papilio gGmbH is the responsible body of all Papilio prevention programmes. We define ourselves as a social company, whose charitable status has been recognised. Papilio was founded in Augsburg (Bavaria) on the 26th of March 2010 as the Papilio e.V. As of the 1st of January 2019, Papilio is now a charitable GmbH. The formal transformation does not influence established contracts.

Being a social company means to us, that we plan our social mission well and implement it strategically. What differentiates us from a commercial business is our purpose: Our goal is not to earn as much money as possible, but to make sure that as many children as possible develop well and in the long run stay protected from risks such as addiction and violence.

A non-profit company such as Papilio gGmbH can only reach its goals with the help of its partners. Without the support of our partners, Papilio would not exist and couldn’t share its preventative approach in pre-schools and primary schools all over Germany.

If you are also interested in becoming a Papilio partner and supporting our mission, then don’t hesitate to contact us:

Katharina Hepke (Chairwoman of the board), tel.: +49 821 4480 5670.

Papilio develops and promotes prevention programmes in nurseries and primary schools.

The programme "Papilio-3to6" for nurseries

- supports social-emotional competence,

- reduces primary behavioural problems and

- protects children from developing problems with addiction and violence.

The programmes Papilio-U3 (nurseries for under 3 year olds) and Papilio-6to9 (primary school) main features have been developed, evaluated scientifically and are now being implemented for the first time.

Responsible body: Papilio g GmbH (charitable) in Augsburg currently has 12 employees

Papilio-3to6 is brought into nurseries through pre-school teachers as mediators

- 234 trainers in 14 states have received advanced training

- 7.745 carers have received advanced training

- 387.250 children profit from Papilio-3to6

- 1.511 nurseries have been reached

In Finland there are 4 active Papilio-3to6 trainers who have coached 507 pre-school teachers in 39 nurseries.

In the German speaking part of East Belgium 5 Papilio-3to6 trainers have coached 175 pedagogues in 35 nurseries.

Papilio-3to6*: A prevention programme for the kindergarten routine

Preventing Behavioural Disorders and Promoting Social-Emotional Competence. Tackling the Risks for Violence and Addiction

This is a short description of the prevention program Papilio-3to6. Papilio has been developed in Germany. It can be adapted to kindergartens all over the world.

For further information please contact:

Katharina Hepke

Am Alten Gaswerk 2

D-86156 Augsburg

Germany

katharina.hepke@papilio.de

phone +49 (0) 821 4480 5670

Papilio follows an approach which holistically and fundamentally supports children’s development. The prevention programme, Papilio-3to6, naturally integrates into kindergarten routine. Aside from the introductory phase, it requires no additional effort but, instead alleviates educational work. Papilio-3to6 works on three levels: with pre-school teachers, the children and parents.

Development supporting parenting

Pre-school teachers** are the central intermediaries of the programme. They educate themselves further on development supporting parenting and implement the Papilio measures with the children and include the parents.

Child focused measures

For children, Papilio-3to6 offers three measures:

- Toys-go-on-holiday day

Children learn to play creatively on their own and with others without conventional playing material. - Mine-yours-ours game

In playful community spirit, children practice and learn social rules and mutual support. - Paula and the pixies in the box

With Paula and the pixies in the box, children get to know the fundamental emotions like anger, sadness, fear and happiness and how to cope with them, concerning others and themselves.

Parent’s discussions, evenings and the ParentsClub

The inclusion of parents is part of the Papilio-3to6 programme: reaching from parent’s discussions to parent’s evenings or the ParentsClub. The latter forms a separate module in the Papilio-3to6 programme: It intensifies the exchange for typical parental obstacles and awards educational partnership between pre-school teachers and parents a whole new quality.

Cultural pedagogy for children

Papilio cooperates with the famous puppet theatre ”Augsburger Puppenkiste“ and other artists. Together they developed several materials:

- the puppet play “Paula and the pixies in the box”

- songs and music,

- two children’s picture books, including education information for parents,

- a radio play “Paula and the pixies in the box”, and

- a DVD “Paula and the pixies in the box”.

Scientific background

Scientific Cooperation Partner for the development and evaluation of the program is Prof. Dr. Herbert Scheithauer, Freie Universität Berlin. Papilio-3to6 was based on a long term study by Webster-Stratton & Taylor, a U.S. American research team.

The effects of the program have been proven by a long term study with 700 children, 1.200 parents and 100 kindergarten teachers.

Why does Papilio-3to6 start so early when at kindergarten age addiction and violence aren’t relevant?

Certain behavioural problems are known as risk factors for the future development of addiction and violence. According to developmental psychology, humans learn fundamental social behaviour at kindergarten age. Measures for the construction of social-emotional competences therefore must start with 3 to 7 year olds. What was neglected or learned incorrectly later is hard to make up for or to correct.

Papilio-3to6 strengthens and supports children and particularly focuses on social-emotional competences, as these are the fundamentals for psycho-social health and the acquisition of many other abilities. In addition they protect against the development of behavioural problems and with that prevent risks such as addictive and violent behaviour. This is the basis for a self-determined and self-dependent life in adulthood.

To reach as many children as possible and support them sustainably, Papilio works with the pre-school teachers** in day-care centres. With further training, the prevention programme, Papilio-3to6, offers concrete measures to effectively support and improve their own teaching behaviour. So far over 7.100 pre-school teachers in Germany have received advanced training with Papilio-3to6.

Papilio-3to6 supports language development day-to-day.

Nowadays child-day-care centres make many high demands and one of them is language training. What is special with Papilio-3to6, is that language training is deliberately integrated in the prevention programme.Thereby, Papilio-3to6 is equally targeted at all children, regardless of their migration background.

Linguistic training is much more than “learning German” or “learning Japanese”: Having distinct language ability is an essential protection factor in the sense of infantile prevention. Children who are good at expressing themselves can introduce and negotiate ideas; they understand others and can make others understand them. The increasingly differentiated linguistic expressiveness is an important basis for social-emotional competence and cognitive development.

Thus, Papilio-3to6 does not foster a separate language learning module but promotes language development in its entirety. No matter the measure – the conscious application of language with pre-school teachers and the linguistic expression of children is an important element of Papilio-3to6.

Major risk factor: Behavioural disorders

Different studies have found that behavioural disorders (such as aggression and withdrawal) are the main risk factors for addiction and violence in adolescence. Moreover the risk factors for addiction and violence resemble those which can also lead to other forms of problematic behaviour.

More risk factors

When behaviour disorders are joined by other risk factors the danger of addictive and violent behaviour later in life increases. Such other risk factors are:

- Lacking bonds with teachers and the school, school failure

- Contact with peers with deficits in social behaviour, exclusion of the peer group

- Ineffective up bringing, lacking supervision, negative quality of attachment towards parents

Behavioural disorders solidify at the approximate age of eight.

Therefore pre-school age is the best chance to positively influence infantile development. This can work in three different ways:

- Minimize risk factors

Risk factors for the development of behaviour disorders are:- Parenting factors (e.g. ineffective parenting practices)

- Child factors (e.g. difficult temper)

- Contextual factors (e.g. adverse psychosocial status)

- Kindergarten or peer factors (e.g. rejection by peers)

- Supporting protective factors and resilience

- Protective factors are friendships, positive peer relationships and positive nursery experiences.

- Resilience is the ability of a child to overcome onerous life circumstances for example through a positive feeling of self worth, self-efficacy beliefs, social behaviour.

- Supporting age-appropriate development

These for example include the recognition of ones own and others fundamental emotions, regulation of emotion and behaviour, learning social rules...

The prevention programme Papilio-3to6 was created on the basis of these findings.

Papilio-3to6 refers to the complex multitude of development factors: The programme reduces risk factors and supports important protective factors as well as age-appropriate development.

Other important aspects

- Papilio-3to6 was designed as one entity: All individual measures are well-balanced and in effect assist each other.

- Papilio-3to6’s measures are applied long term and recurrently as that is the reason it takes effect permanently. Individual actions do not prove themselves to be sustainable. A study has proven that Papilio-3to6 measures are applicable in nursery routines.

- The programme Papilio-3to6 connects pedagogy and developmental psychology, which means: Pedagogic content and the time and nature of its mediation have been optimally coordinated.

In the following, behavioural problems such as emotional and social problems, which children at pre-school age can have will be described. If these problems occur long-term, they can prevent children from participating appropriately in events typical for their age, endanger their development and in the worst case scenario, lead to behavioural disorders in childhood.

Selected study results concerning frequency

Behavioural emotional and social problems at the ages of 3 to 6 years old, e.g. oppositional defiant and aggressive behaviour, but also fear and social retreat, occur relatively frequently:

- In a survey for parents on the behaviour of their 4 to 10 year olds parents very frequently reported aggressive and problematic behaviour: 29.7% of boys and 25.6% of girls show at least one aggressive and pronounced behavioural problem. 18.9% of boys and 16.3% of girls exhibit at least one pronounced symptom in the area of ‘attention problems’. Other problematic behaviour or social and emotional problems (social retreat, bodily problems, shyness/depression, social problems, schizoid/compulsive behaviour and anti-social behaviour), with at least 3-12.5% of children showing one significant symptom.

- Concerning oppositional behaviour international studies show a prevalence rate of 7-25% of children at pre-school age. In the German language speaking area, scientists have determined that 13.5% of parents have the problem of their children not obeying orders at least once a day. 5.6% of children have fits of rage in families. In pre-schools, carers report oppositional behavioural patterns with only 2.5% of children and only 0.4% are reported to have fits of rage. It is estimated that children are experienced as more problematic in the family than in pre-school.

- In a different study, 23-30% of parents report fits of rage with their children and up to 20% of parents say that their children show physically aggressive behaviour towards them. Hyperactivity and attention problems are also reported frequently. In total 13-17% of 3-6 year olds exhibit behavioural problems at a clinically significant scale. These early emerging externalised behavioural problems are therefore not only short lived: Particularly aggressive and hyperactive behavioural problems of 3-6 year olds have been relatively stable over 2 years.

- According to parents estimations, nearly half of all behaviour problems are settled in the area of oppositional and attention seeking behaviour, says another study. Hyperactive behaviour and uncertainty during social interactions are also frequently represented. Around 18% of children in kindergarten suffer from emotional and behavioural disorders which are in need of treatment.

Some of these problems, which are ‘directed outward’ (externalized problems such as aggressive behaviour, impulsivity, hyperactivity), on the other hand can be discovered more clearly and easily than problems which are directed inward (internalized problems such as fear disorders or ongoing sadness).

Basically it is important to be able to discern between occasionally occurring difficult behaviour on the one hand and behavioural disorders on the other hand. Not every child that hits another child in certain situations is showing a social behaviour disorder and many children have fears in certain situations without have a fear disorder.

The term behavioural disorder in clinical children’s psychology does not describe a single problematic behaviour. Most of the time it is a bundle of problematic behavioural patterns, which occur repeatedly and at a certain intensity. In addition, these emerging problems in the child’s routine are also so strong, that a normal development would be at risk of being jeopardised.

Most disorders in childhood are not in the area of clearly circumscribable diagnostic disorder categories which would impede a precise description and definite assignation and could only be enabled if the children would be observed repeatedly and in varying situations. Therefore behavioural patterns in respect of their intensity or frequency can either occur

- too strong (behaviour excesses, e.g. aggression, motoric unrest) or

- too weak (behaviour deficits, e.g. social retreat).

With children, age and developmental status must always be taken into account. Aggressive behaviour and certain fears are ‘completely normal’ with very many children. One example for this would be, being shy with strangers, which many children are at two years old. Aggressive behaviour such as e.g. hitting or taking away toys is quite frequent at three years of age.

Aggressive behaviour in childhood

To be discerned are two disorders whose common aspect is aggressive behaviour:

- Social behaviour disorders

Characteristic is a repetitive and persistent pattern of dissocial, aggressive and rebellious behaviour. This problematic behaviour exceeds the age appropriate expectations and is thus more severe than ordinary childish mischief. A disorder is only diagnosed when the problem behaviour patterns occur for longer than 6 months. Occasional aggressive and oppositional behaviour must be discerned from this. That can also be the expression of tiredness or stress. Therefore, it is important to observe children not just once, but for a few days or weeks in different situations and in combination with varying people, other children etc., before you can be sure that ongoing problems are at hand. - Social behaviour disorder and oppositional defiant behaviour

This behaviour usually occurs with younger children. Characteristic for this is clearly rebellious, disobedient behaviour, however without criminal actions or severe forms of aggressive or dissocial behaviour. Moreover, there are varying levels of difficulty e.g. low, middle and high depending on the number or intensity of symptoms and caused harm and negative effects for third parties.

Furthermore, there are different disorders during childhood and youth that can go hand in hand with aggressive behaviour, but it isn’t the central problem.

Furthermore, social disorders are often connected to the appearance of further disorders e.g. attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) or rather hyperkinetic disorders or problems of impulsivity or attention. Deciding if a child’s impulsive behaviour through inattention should be categorised as aggressive is not easy. It is important to recognise that with aggressive behaviour there must be malice that comes with it. This is not the case in children with ADHD.

Less frequently, but still more frequently than with psychologically healthy children, sadness and social retreat can occur. This can be traced back to the children often having conflicts with their parents and other people and they are often rejected by peers.

Socially insecure behaviour in childhood

Next to children with aggressive or defiant behaviour, children that are socially insecure often don’t attract attention. It is not uncommon for them to step into the background in a group of inconspicuous children, giving the impression of being easily cared for. Socially insecure children are often described with the terms ‘shy’ or ‘inhibited’. They speak only a little or very quietly, hide behind other and avoid eye contact. Facial expressions and gestures often seem reduced. Behind socially insecure behaviour there can be a variety of fears.

The most common fears in childhood are:

- Separation anxiety

A strong fear of being separated from ones' attachment figure. This can be expressed through the children refusing to stay at home alone or going somewhere else on their own. The children are often worried that something bad could happen to their attachment figure. In addition, bodily symptoms such as tummy/head aches or nausea can occur in situations that are connected to the separation. To be discerned from this are normal reactions towards separation from attachment figures, which especially occur with younger children and are also referred to as ‘being shy with strangers’. - Social fears/social phobia

Ongoing fear of unfamiliar grown ups and/or peers. This fear is so strong that children try to avoid contact with unfamiliar people. When this isn’t possible the children are clearly timid. All in all social relationships, apart from those towards main attachment figures, are strongly impaired. - Generalised fears

Several strong fears that relate to different incidents or activities. The children are often dominated by their fears and seem restless or nervous, accompanied by fatigue, lack of concentration and sleep disturbances. These fears are not limited to only one situation, like fear of separation.

Socially insecure and shy children are scared of being rated negatively by others, making a fool of themselves or failing. They are scared of encounters with several people or strangers. They avoid social contacts, it is hard for them to build up friendships and they are often rejected by peers or rather count as unpopular. In game situations they don’t participate, often just watch and don’t dare to bring in own ideas and needs.

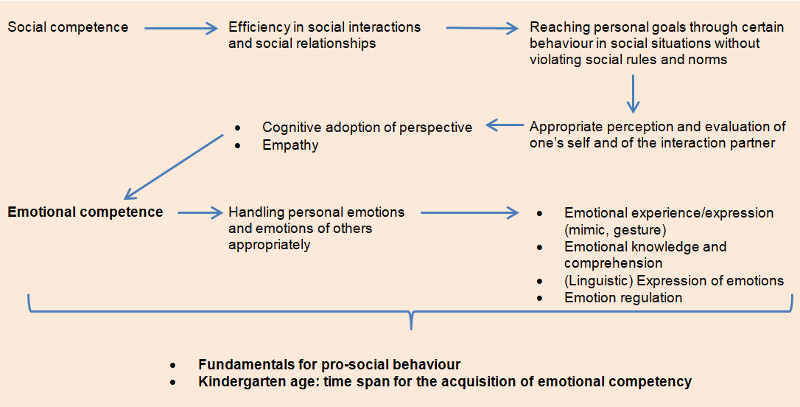

Emotional und social competences are closely linked and influence the quality of our social relationships immensely. For example, they determine how well we can deal with our own and other people’s emotions and tackle social conflicts. The acquirement of emotional and social competences is an important developmental task of pre-school education and the base for psychosocial health.

Comparing socially competent and socially incompetent

The meaning of social competence becomes very clear when observing the varying behaviour of socially competent children and children who lack social competences.

| Socially competent children | Socially incompetent children |

| Successful assimilation to the social environment | Behavioural problems, like aggression at pre-school age |

| Positive peer relationships | Few relationships with peers |

| Positive relationships with carers/teachers | ADHD |

| Pro-social behaviour (e.g. sharing, cooperating, social interaction) | Limited pro-social behaviour |

| Extreme forms of shyness |

Social and emotional competences are of extreme importance. The lack of these competences is supposed to be the origin of many problems. Therefore, certain measures are taken for the support of the development of social and emotional competences in therapy and prevention of various psychological problems in children. Studies on the effectiveness of these measures confirm an improvement in emotional and social skills and abilities and a reduction in behavioural problems.

Abilities and skills

Abilities refer to fundamental potentials (e.g. concerning communication, movement, thinking) enabling us to handle our environment with competence. They are seen as requirements for the realisation of a skill.

Skills prove to be more specific than abilities; they represent a learned or acquired part of behaviour and are strengthened through exercise and practice.

Following you find further information on the topics:

- Fundamental concepts for the constructs of ‘emotional’ and ‘social competence’ and their relationship towards positive and negative courses of development in children

- Relationship between emotional and social competence

- Influencing factors on the development of social and emotional competence in children

Emotions are short lived temporary states of mind and are understood as reactions to external events. They go hand in hand with physiological (bodily) reactions and influence what and how quickly we perceive things, how we react to certain sensory impressions and what we think of while reacting. Emotions influence our daily actions, shape our every-day lives and decisively form the quality of social interactions and relationships with other people.

The developmental duty of emotional competence

Children first have to learn how to interact with their own, and others, emotions. Due to the distinguished significance of emotions for social interactions, the acquisition of emotional competence counts as one of the most important developmental duties at infant and pre-school age. It is a basis for other developmental areas and helps cultivate them.

Definition of emotional competence

In general, emotional competence can be understood as the ability to appropriately deal with your own, and other people’s, emotions. Developmental psychology defines it even more precisely, as emotional competence requires a variety of skills:

- Personal facial expression of emotions

- Recognition of other peoples mimic expression of emotions

- Verbal expression of emotions

- Emotional knowledge and understanding

- Emotion regulation

Personal mimic expression of emotions

Children must learn how to appropriately express emotions through mimic and gesture, so that other people are able to recognise their emotional state.

In the following course of development they should learn to separate their subjective perception of emotion from the expression of emotion, as required. This applies to situations in which actual emotions should not be shown due to societal conventions or personal interests. Children begin to understand the differentiation between emotion experience and emotion expression at around 3 years old. At this point they also begin to adjust their expression of emotion according to the situation and use it strategically.

Recognition of another’s mimic expression of emotions

For a successful interaction with other people, recognising their emotions is important. When children are able to read what their counterpart is feeling they can adjust their actions accordingly. Children that are able to read peoples emotions well are more popular with other children.

Linguistic expression of emotions, emotional knowledge and understanding

The linguistic expression of emotion encompasses the ability to describe, and with that, convey one’s emotions. This requires elaborate emotional knowledge and understanding.

Children with an elaborate emotional knowledge can describe their emotions more easily, and with that, convey their needs. Children with little emotional knowledge struggle to express their emotions, and with that, their cohering needs. When a child with few skills is angry while linguistically expressing emotion, it is more likely to show socially inappropriate behaviour (such as taking away toys or hitting someone) than children who have the ability to solve a conflict through linguistic notification.

Furthermore, comprehension and knowledge of emotions form the basis for development of empathy and pro-social behaviour.

At the age of 2-5 years old, particularly many links between emotions and cognitions are created. The pre-school age is a sensitive phase in which emotion-cognition-links must be supported. These skills form the basis for learning emotion regulation.

Emotion regulation

The regulation of emotion refers to a child’s strategy to handle its emotions. This encompasses the following skills:

- Establishment and maintenance of emotions

- Control and modulation of intensity and duration of emotions

- Physiological processes and (bodily reactions) behavioural patterns

Emotion (dys) regulation coincides with a common behaviour, which to a certain degree is part of children’s development: temper tantrums.

With fits of rage and tantrums, developmental changes in emotion regulation become visible. Tantrums occur frequently at the age of two and become less frequent during the course of development. Characteristic for tantrums is the enormous intensity with which children express their anger. The children experience their emotions so strongly, that they are not receptive to peaceable words.

When tantrums are still frequent with an older child, lacking control and modulation of the intensity and duration of the emotions suggests itself. In a situation like that, thinking and the behaviour of children is restricted. When faced with interpersonal problems children are less likely to come up with solutions and implement them. Children lacking emotion regulation show less pro-social behaviour, are more aggressive and are often rejected by their peers.

Just as ʽemotional competenceʼ, the theoretical construct of ʽsocial competenceʼ has different aspects.

Definition of social competence

On a very general level, social competence can be defined as efficiency in social interactions. Efficiency here refers to reaching personal goals in social situations while following general social rules and norms.

More elaborately defined, social competence is an individual’s skill in reaching personal goals in social interactions while, over time and varying situations, upholding positive relationships with others. This definition emphasizes the ability of conserving positive social relationships.

Social competence is presented as a general comprehensive competence because it describes the ability of upholding positive social relationships.

Thus, social competence includes a multitude of social skills, behavioural patterns and competences that relate to challenges in a social environment, which a person can successfully implement.

Pre-condition: Being able to distinguish yourself from others

For socially competent actions, all definitions fundamentally pre-suppose the cognitive ability to discern yourself from others. This shows a close connection between social and cognitive development in the first years of life, as this discerning ability develops at the age of two.

Therefore, pre-school age is the deciding phase of life-important social abilities in which skills are developed and further differentiated.

Being able to distinguish yourself from others enables self-awareness and the ability of cognitive adoption of other roles and perspectives. Both of these are requirements for empathy, which can show itself in pro-social actions (helping or comforting).

Cognitive adoption of perspective and empathy

Empathy describes an emotional reaction evoked by the affective state or situation of another person and describes the compassionate feeling towards them. Generally, empathy can be divided into two levels, which however overlap and can’t always be differentiated:

- Cognitive level: Being aware of another persons emotions and being able to mentally put oneself into their position (cognitive adoption of perspective)

- Emotional level: Representative affective reaction to emotions of the other person, to sympathise and the arising action impulse to help change the suffering or the situation of another person.

A whole range of scientists have grappled with social competence; hence, there are varying approaches of description.

Rose-Krasnor (1997) for example divides social competence into three dimensions:

- Knowledge related competence (culturally specific information on the fundamental rules of interpersonal cooperation)

- Abilities (fundamental, social abilities not restricted to certain situations) and

- Skills (specific, concrete, situation-bound, learned behaviour patterns that are dependent on the fundamental abilities)

Kanning (2009)

- Perceptive-cognitive area: Self-awareness, social perception, adoption of perspective, locus of control, decisiveness, knowledge

- Motivational-emotional area: emotional stability, pro-sociality, value pluralism

- Behavioural area: extroversion, assertiveness, action flexibility, style of communication, conflict behaviour, self-monitoring

Eisenberg und Harris (1984) describe social competence in a minimum of five aspects:

- Ability to adopt perspective

- Recognising the importance of friendships

- Development of positive problem solving strategies within social interactions

- Development of moral ideals

- Communication skills

Caldarella und Merrell (1997) after an analysis of several studies, describe which abilities and skills social competence in children can be detected with. They conclude that there are five dimensions of social competence:

- Skills for the creation of positive relationships with peers, (amongst others, social adoption of perspective, helping or praising others

- Self management competences (such as overcoming conflicts or regulating your own mood)

- Academic competences (listening to the teacher’s instructions, asking for help)

- Cooperative competences (acknowledgment of social rules, showing appropriate reactions to criticism)

- Positive self-assertion and assertiveness (initiating conversations or activities)

Pro-social behaviour

Pro-social behaviour encompasses behavioural patterns like sympathy, helping and collaboration to the benefit of the group. We are talking about skills on which basis other people benefit from, (pro-social behaviour). A lack of these skills could, for example, lead to others being harmed (dissocial or aggressive behaviour). These skills, or lack thereof, develop in context of social interactions. Hereby, the peer group has an important function. Social competences are a requirement for pro-social behaviour.

Emotional and social competence stand in close and versatile relation to each other. Certain emotional skills are the basis for socially competent behaviour. High emotional competence goes hand in hand with a higher social competence and fewer problems with peers. For example, five year olds who are able to recognize and name others mimic emotions have a more pronounced positive social behaviour and more frequent social contacts with peers.

Emotions form the motivational basis for empathy and pro-social behaviour just as well as for anger, which in the worst case can result in violent behaviour. Emotional competence, for example, strengthens the social adoption of perspective, meaning a child can imagine more clearly how other children are feeling. Therefore, emotionally competent children are usually more popular with other children and less aggressive.

Children with little emotional competence however, appear to lack social competence and show externalized conduct disorders more frequently. Studies have found that children with social and emotional problems tend to have weaknesses in the field of emotional competence.

Frightened children tend to have a limited repertoire of possible mimic expressions and are more unsure when interpreting the emotions of others.

Children with aggressive behaviour stand out more frequently for their restricted emotional competence.

Children who have problems regulating their emotions and handling their emotions constructively are more likely to be rejected by peers and seen as less socially competent.

Lack of skills with perception and description of emotions go hand in hand with being rejected by other children. When a child doesn’t understand the emotions of another it can lead to misunderstandings and conflicts. Appropriate anger regulation strategies on the other hand can work against the appearance of behavioural disorders.

As emotional and social competences are closely linked, social and emotional competences and social-emotional skills are often talked about, as a result.

Scientists have compiled a series of social-emotional key skills recommended through programmes for emotional and social learning:

Self awareness and awareness of others

| Perception of own emotions | Correctly perceiving and naming ones own emotions |

| Regulation of emotions | Being able to change ones emotions (e.g. changing their intensity) |

| Positive self-perception | Recognising strengths and weaknesses and facing every day challenges with confidence and optimism |

| Adoption of perspective | Recognising the perception of others |

Social interaction

| Active listening | To turn to others and show them that they are being understood |

| Communication | Initiating and keeping conversation alive as well as expressing thoughts and emotions verbally and non-verbally |

| Cooperation | Sharing and taking turns with others |

| Negotiations | different perspectives to reach a solution that pleases everyone |

| Refusal | Refusing and not letting yourself be put under pressure |

| Search for support | Recognizing a need for support |

With a support of these social-emotional key skills, the risk for emotional problems (such as fear and social retreat) or behavioural problems (e.g. aggressive dissocial behaviour) can be reduced. The successful composition of social emotional competences is a requirement for a psychologically healthy development of children. Building upon these competences, children show prosocial behaviour, such as for example, assistance.

Children with social-emotional competencies have shown to integrate easier into a group of peers and adapt better to new challenges (e.g. in school). Children with a high level of social-emotional competence come to attention less frequently on account of behavioural problems.

On the other hand poorly developed social-emotional competences are a significant risk factor for a variety of problems (such as aggressive-dissocial behaviour).

Children’s temper

An early active influencing factor on the infantile social and emotional development, is a child’s temper. Generally, temper can be understood as how children act or react: temper does not describe what a child does (behaviour) but how it does something.

It’s about behavioural tendencies that over certain periods of time and varying situations stay relatively constant, for example in regards to bodily adaptive responsiveness or emotionality.

"Difficult temper"

A certain combination of temper characteristics are often described as “difficult” temper. This is what children who are easily irritated, have an irregular biological rhythm and frequently show negative emotions, are labelled as. These temper characteristic constellations are connected to oppositional and aggressive behaviour during infancy and in the long run, aggressive dissocial behaviour throughout adolescence.

We explicitly highlight that there is no such thing as a ʽdifficultʼ temper, but that there are possible problems and risks in infantile development which can appear due to the fact that, the environment of the child does not fit its temper characteristic. So, for example, parents have diverging expectations towards their child or can’t cope with a very lively child and then feel overburdened. Through these situations, problems arise during interactions between the child and its parents.

"Inhibited temper"

Children with ʽinhibitedʼ temper attract attention because they find it harder to adapt to new situations or unfamiliar people. These children are more likely to retreat and feel afraid. Children with a strong behavioural inhibition are at higher risk for anxiety disorders.

Linguistic development of children

The linguistic development of children is closely tied to social competence or rather difficulties in social interactions, because language has a fundamental function in creating and maintaining interpersonal contacts. Children with language development disorders have increased emotional or behavioural problems. So it is interpreted that, children are more likely to react aggressively when they aren’t able to express their wants and needs, but still want to reach their goal (for example receiving a toy).

Parent-child interaction

Parental, (especially maternal) characteristics influence the social and emotional development of children. An essential factor of influence is the quality of early parent-child interactions. The term interaction already highlights that the attention is not on one-sided behaviour of either the attachment figure or the child, but the process of social exchange.

Familial influences and parenting are reflected in mother-child-interactions. The most important influencing factors on emotional, and with that, also social development are:

- Emotional family climate

How do family members express their emotions? - Parents’ emotional expression

Parents are role models for children concerning the expression of positive and negative emotions, and with that, regulate the emotional experiences of their children who in emotional situations orientate themselves towards the reactions of their attachment figures. - Responsivity of parents

Parents who react to childish emotions in a sensitive way, meaning they don’t suppress the emotions but cater to the positive and negative emotions of children, support exactly such behaviour in their children in relation to others. - Emotion Talk

Conversations between parents on emotions, their origins, consequences as well as their connections to behaviour and thoughts that go along with them, promote the emotional and social development of children. Children have a wider emotional knowledge and understanding and can regulate their emotions more easily when their parents talk to them about emotions. - Handling negative emotions

For the emotional development of the child, frequent expression of negative emotions like anger and sadness are disadvantageous. Children then also show negative emotions more frequently, to which parents react to with stern and rejecting behaviour. Thus, negative emotions build up with the parents and the child while long-term expression of negative emotion will become especially pronounced. Parents, who frequently show positive emotions while interacting with their child as well as a characterized affectionate attitude towards their child, tend to have children that react with empathy to negative emotions of other children and show less behavioural problems. - Co-regulation of emotions

Parenting

A warm, parenting attitude characterized by affection in combination with a consistent and consequent parental behaviour, supports a positive development of children. Severe disciplining techniques, physical punishment, little parental attention or predictable behaviour, on the other hand, correlates with spiteful and aggressive, but also shy and reserved behaviour in children. The latter also occurs with an overprotective and overstimulated style of parenting.

Mother-child-interactions and parental behaviour play an especially important role in the emotional and social development of a child. The competences a child builds up at home, determine its skills when establishing social relationships with peers. The patterns of interaction learned at home are initially transferred to social interactions with pre-school teachers or peers – then over time will be altered by the experiences with educators and peers.

Social competences and contact with peers

Contact with peers plays an important role for the development of social competence and influences the development long term. For this reason, entering play school is so important for children in our western society. For many children, this is the first time they can play with (several) peers or rather equals. Whilst interacting with peers, children must confront the topic of justice. They have to learn to share toys or be patient till it is their turn. Playing together is especially important for the development of social competency is. Here children can learn to coordinate their own and others needs. Playing together supports social adoption of perspective, a central requirement for the adjustment of ones own actions to the needs of others.

Often first friendships are formed in day-care centres. Depending on the stage of development, the term “friendship” is defined differently. Friendships between 3-4 years olds result from communal games. Common stances or belonging to a certain group are not paramount yet. These forms of friendship though are the base for later friendly relationships.

The construction of stable friendships and the development of social competence influence one another: Social competence significantly influences the skills a child has for building stable friendships. On the other hand, children practice and develop social competence within the scope of friendships. Children with few social competences, who can’t build friendships, are in danger of increasing their developmental deficit. In the long run, this can result in the children retreating as much as possible from social situations and/or being rejected by other children for behaving inappropriately. Therefore, they are at higher risk for aberrations such as social fears or aggressive behaviour.

A lack of social competence and friendships are therefore risk conditions for the further development of children. Positive relationships with peers are a protective condition for children. Scientists were able to show that five year olds from unfavourable familial circumstances develop in a positive way, when they are accepted by peers and have stable friendships with other children. Children from adverse familial circumstances, with no stable friendships, who were being rejected by peers on the other hand, stood out in school for aggressive and hyperactive behavioural problems.

Eisenberg, N. & Harris, J.D. (1984). Social competence: A developmental perspective. School Psychology Review, 13, 267-277.

Kanning, U.P. (2002). Soziale Kompetenz - Definition, Strukturen und Prozesse. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 210 (4), 154-163.

Rose-Krasnor, L. (1997). The nature of social competence. New York: Guilford.

Rose-Krasnor, L. (1997). The nature of social competence: A theoretical review. Social Development, 6 (1), 111-136.

Rubin, K.H. & Rose-Krasnor, L. (1992). Interpersonal problem solving and social competence in children. In V. VanHasselt & M. Hersen (Eds.), Handbook of social development (pp. 283-323). New York: Plenum.

Zahn-Waxler, C., Radke-Yarrow, M., Wagner, E., & Chapman, M. (1992). Development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 28, 126-136.

For further information please contact:

Katharina Hepke

Am Alten Gaswerk 2

D-86156 Augsburg

Germany

katharina.hepke@papilio.de

phone +49 (0) 821 4480 5670

* The prevention programme used to be just called ʽPapilioʼ. Now that we have created further programmes for under three year olds and for the transition to primary-school, we have given the kindergarten programme the more precise name of Papilio-3to6.

**By pre-school teachers/carers we mean all pedagogic specialists in child day-care centres.